Dangerous Fur (2016)

Danger is not something external to ourselves that we can eradicate from our lives.

>> Flickr set

Our bodies evolved over millions of years to survive an environment shaped by natural forces. We’ve used our bodies to modify this environment, building tools, technology, infrastructure and community to overcome the dangers that threatened our survival. Today our bodies survive the dangers of the built environment we’ve created.

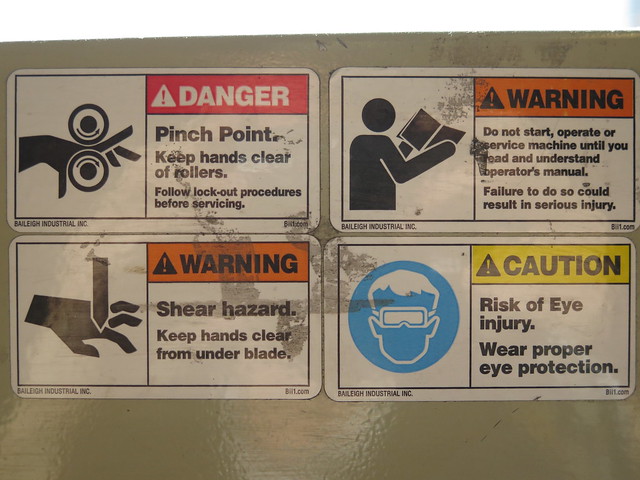

Walls, railings, enclosures, protective clothing, preventive drugs are all there to protect us from physical harm. We live in a world in which it is okay to interact with almost everything. And if not, then we trust that our governing bodies have put laws in place to protect us. Poisonous items will be labeled, slippery surfaces signposted, the radio frequencies from our cellphones will not be cancerous, the plastic encasing our laptop will not be toxic and superglue will not be sold to children.

Yet we seek out situations that take us outside this constrained world of Health and Safety in order to experience danger. Extreme sports are an example of our desire to face the unknown and uncontrollable elements of nature. By facing the possibility of getting hurt, we are forced to make our own decisions.

Dangerous Fur adds an instance of physical harm to our interactions with the built environment. Making our body vulnerable to pain by lining it with a series of mechanical and electrical hairs that can seriously hurt us. Even in the safest of situations it threatens us with danger.

Background

This project proposal emerges from my fascination with how we’ve used our human ability and skill to shape the world around us. In order to do so we developed many hand tools that allowed for a risky process, meaning we could mess up at any point. Machine tools imply a process of certainty, aimed at mitigating such risk. In order to command these certain processes we use interfaces of certainty. Our hands become tools for translating our ideas from mind to computer. Danger is mitigated by Ctrl+Z. Pressing buttons and moving the mouse are entirely safe interactions. The buttons won’t shock us, the mouse won’t nibble at our fingers. There is no danger, no moment of fear. I want to work with these machines on a more risky level. Dangerous Fur is not a practical answer to this desire, but rather a wearable opportunity for dangerous engagements with a very safe world.

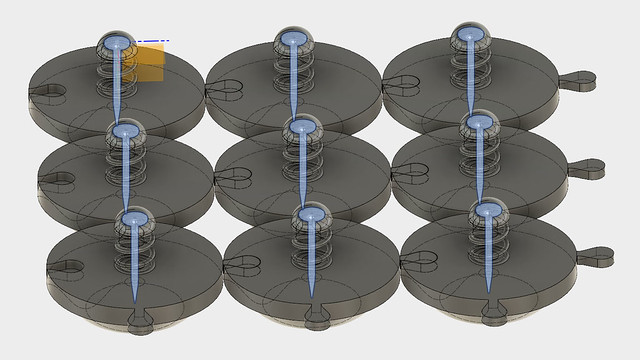

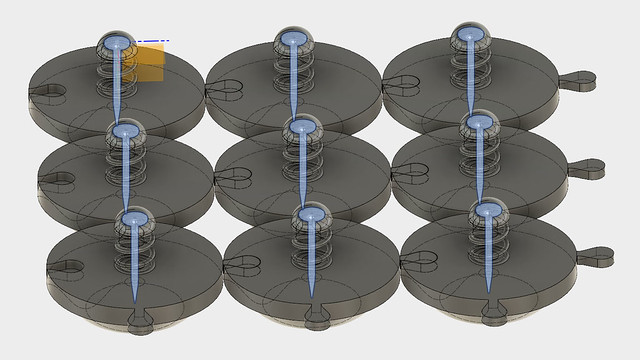

Technical Specifications

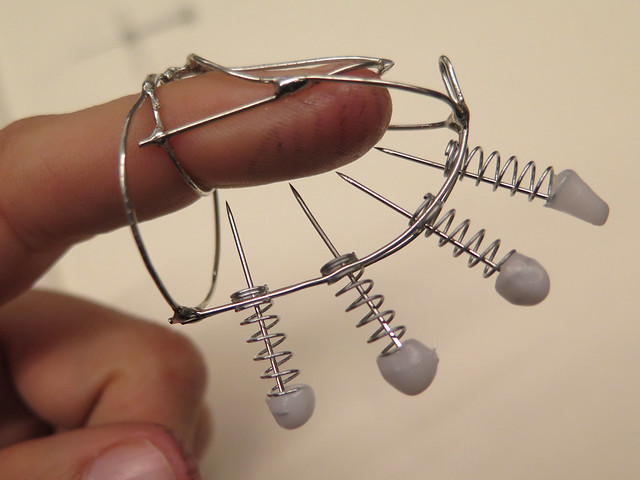

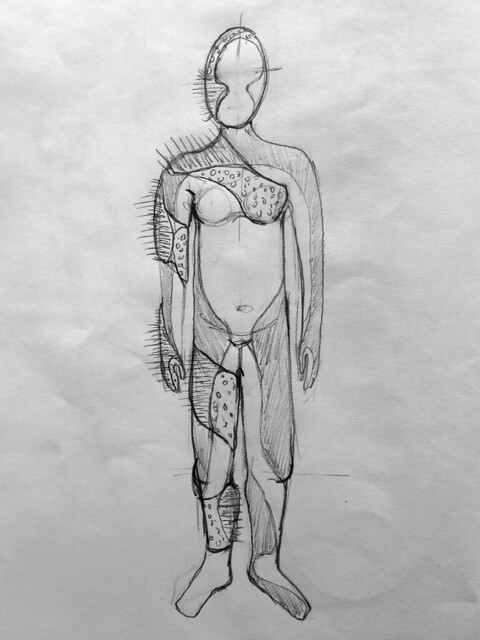

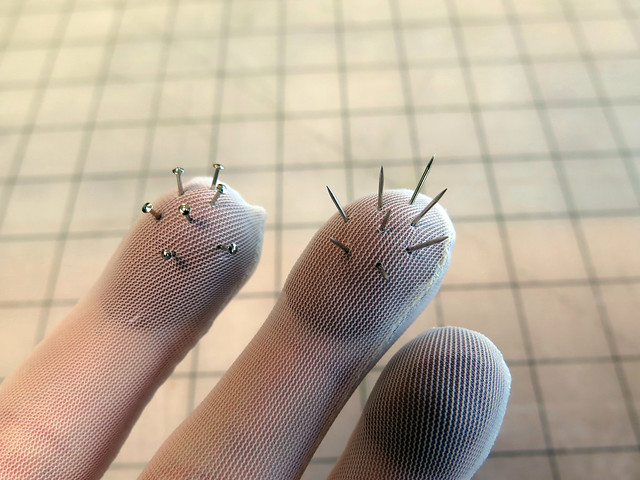

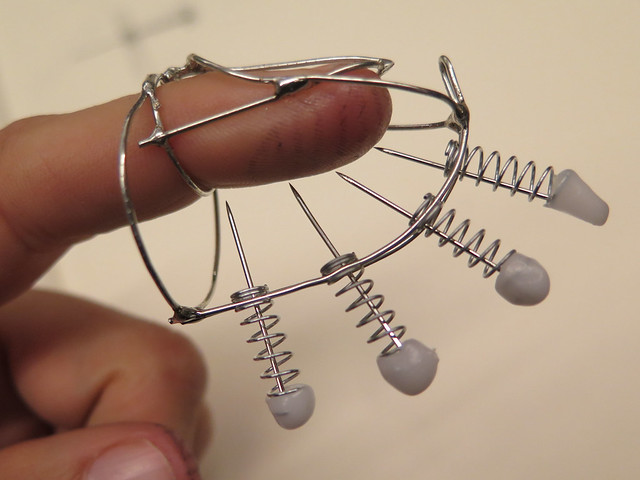

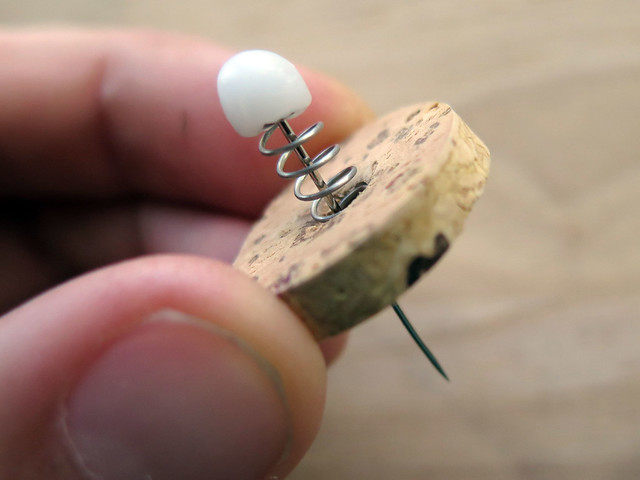

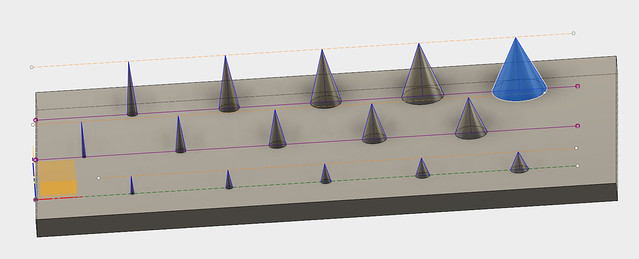

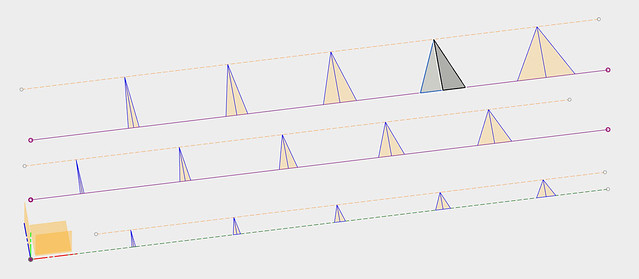

Dangerous Fur is a man-made fur structure assembled from dress pins, 3D printed textile and integrated circuitry. The link to the Flickr set shows sketches and images of my first prototypes that lead to the idea. I imagine the final design to look much more technical (less steam punk). The fur should be a densely populated material that can be tailored like fabric to produce a series of wearable fur accessories such as gloves, shoulder and leg wraps.

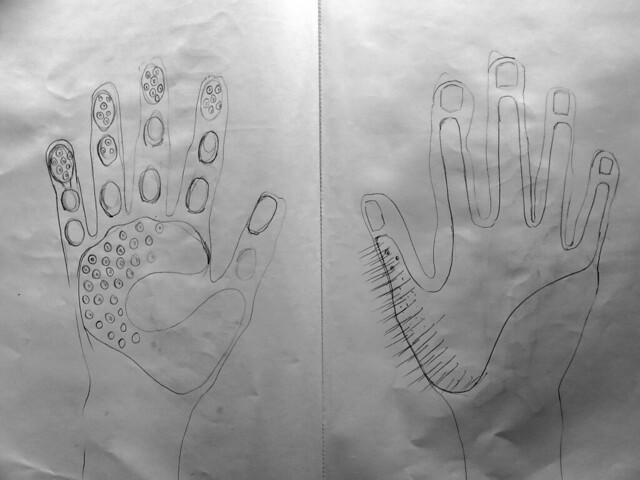

In my current thinking the fur actually consists of two kinds of fur that address different parts of our body in terms of what surfaces we actively use to touch, and which surfaces passively receive touch.

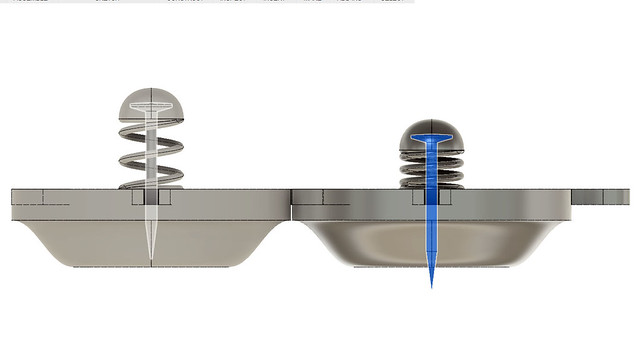

Inner fur: is applied to the inner surfaces of the body such as the palm of the hand and the chest. It is a purely mechanical construction consisting of suspended dress pins pointing towards our skin. Even the slightest pressure exerted on the fur will cause the pins to contact the skin. The amount of pressure required to press the key on a keyboard results in the pin piercing the first layer of skin.

Outer fur: applied to the outer surfaces of our body such as the back of the hand and the shoulder. A fury needle structure made up of dress pins that are internally wired up as electrodes to a circuit that will cause an electric shock to the body when two needles touch because the fur was stroked or brushed against a surface.

Notes

Many “modern” ways of manipulating the built environment eradicate the skill and dexterity of the human hand from the equation. Instead interfaces require our hands only as input mechanisms to translate our human brain capacity into machine language. Dangerous Fur seeks to bring the hand, the body, the sensory organ back into the digital manipulation process.

Our hands are our primary tools for manipulating materials to manufacture. Machine tools move our manual manipulations away from being a risky process, towards becoming more and more certain. In order to translate our intentions into reality using many of the highest tech manufacturing tools such as 5axis mills, laths, knitting machines, looms… our hands play the role of translating our creative abilities from our minds on to computers that will control the machines. The instance of clicking the mouse button or typing on a keyboard are extremely certain interactions. There is no danger, Control z, undo…

The initial ideas for a Dangerous Fur came during a 4-month residency at Autodesk’s Pier 9.

Dangerous Fur

A wearable opportunity for dangerous engagements with a very safe world.

Our bodies evolved over millions of years to survive an environment shaped by natural forces. We’ve used our bodies to modify this environment, building tools, technology, infrastructure and community to overcome the dangers that threatened our survival. Today our bodies survive the dangers of the built environment we’ve created.>> https://www.flickr.com/photos/plusea/sets/72157666161511975

Sharpness?

What makes something sharp != What makes something dangerous

Its about force multiplication. The thinner the edge, the more the focused the force, and the higher the pressure. At enough pressure, a material will give way. A wedge shape can both multiple the force and drive the material apart, further cutting it. A duller knife has a thicker end, and hence requires more force.

>> https://www.quora.com/What-makes-an-object-sharp-enough-to-cut-Why-can-regular-paper-cut-you-but-not-cardboard

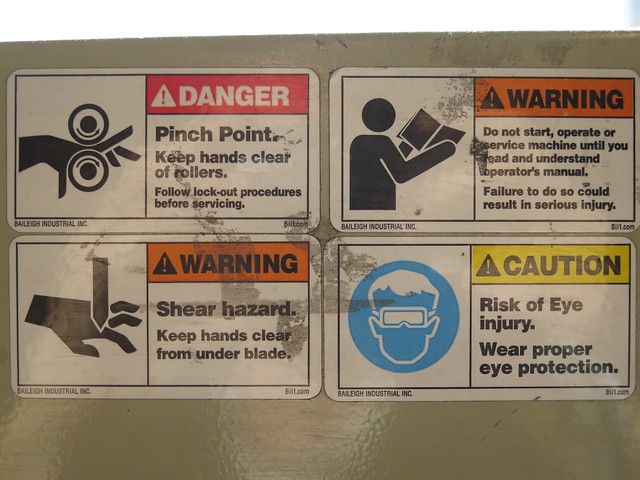

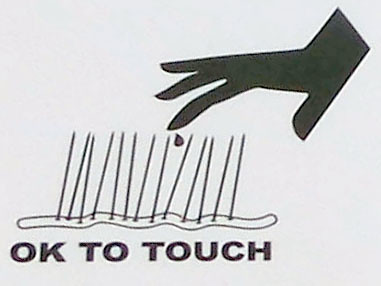

DANGER / OK TO TOUCH

Danger is not something external to ourselves that we can eradicate from our lives.

A pin is a device used for fastening objects or material together. Pins often have two components: a long body and sharp tip made of steel, or occasionally copper or brass, and a larger head often made of plastic. The sharpened body penetrates the material, while the larger head provides a driving surface. It is formed by drawing out a thin wire, sharpening the tip, and adding a head. Nails are related, but are typically larger. In machines and engineering, pins are commonly used as pivots, hinges, shafts, jigs, and fixtures to locate or hold parts. Pins hurt.

>> https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pin

The Pin Factory

An 18th Century Pin Factory from the Encyclopédie edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, 1751–72.

>> http://platypus1917.org/2013/11/01/adam-smith-revolutionary/

In the first sentence of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith foresaw the essence of industrialism by determining that division of labour represents a quantitative increase in productivity. Like du Monceau, his example was the making of pins.

>> https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Division_of_labour

Book I, Chapter 1. Of the Division of Labor: THE greatest improvement in the productive powers of labor, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which it is anywhere directed, or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labor….To take an example, therefore, the trade of the pin-maker;

>> http://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/adamsmith-summary.asp

Adam Smith’s pin factory example is an application of his theory of division of labour. Smith argued that humans can ‘specialize’ their skills in order to create greater aggregate human prosperity. The pin factory is a specific example of how labourers can specialize within even menial tasks such as pin manufacturing in order to increase productivity.

>> https://www.quora.com/What-is-so-important-about-Adam-Smiths-pin-factory-example

Adam Smith’s Wealth Of Nations reference to pin making overshadowed the broader significance of this “trifling manufacture”, which had been “very often taken notice of”. Paucelle (2007) traced Smith’s sources to Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopedie (1755), Duhamel’s Arts & Metiers (1761), and Macquer’s Dictionnaire portatif (1766), all detailing the long-established manufacture of L’Epingles (Pins). Smith used these details to illustrate the direct association of the division of labour with sustained increases in productivity, leading to the wider consumption of the “necessaries and conveniences of life”, and, we now know, to unprecedented living standards in market societies.

>> https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/economics/of-pins-and-things

One man draws out the wire, another straightens it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving, the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some factories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometimes perform two or three of them.

In traditional manufacture, with each man performing all the steps, they would be hard pressed to produce 20 in a day. As described by Smith, the task of making a pin was broken down to eighteen distinct operations, which were all performed by distinct hands. Smith goes on to point out that he had observed small factories of some 10 men who, engaged in the detailed division of labor, could produce some 48,000 pins a day. This would amount to some 4,800 pins for each man, a significant increase in productivity.

>> http://www.faculty.rsu.edu/users/f/felwell/www/Theorists/Essays/Braverman1.htm

How It’s Made – Needles & Pins

Others Works

Mona Hatoum’s Pin Carpet

>> http://www.fabricworkshopandmuseum.org/Artists

>> https://www.icaboston.org/art/mona-hatoum/pin-rug

/ArtistDetail.aspx?ArtistId=20816cd7-3ae0-4c7d-9f89-d099ca2f6e94

Bart Hess Metal Fur

During milan design week 2014 dutch fashion / material designer bart hess is presenting a sequel to the installation ‘work with me people’ by MU during dutch design week 2012. for this occasion, hess installed a sweatshop-like intervention where dozens of visitors work on the various textiles for products that are distributed among bart’s international clientele. ‘work with me people’ refers to the discrepancy between, on the one hand, the post-fordian creative industry, and on the other the huge amount of work required to sustain it. the innovative format of the project offers insight into the production process of the couture textiles by hess and invites visitors to take part in making them.

>> http://www.designboom.com/design/bart-hess-work-with-me-people-04-15-2014/

>> https://vimeo.com/82293548

>> http://barthess.nl/wwmp.html

Susie MacMurray’s Widdow and Wax and Pins

>> http://www.susie-macmurray.co.uk/images/garment-sculptures/widow

>> http://www.susie-macmurray.co.uk/images/sculptures/wax-and-pins